The best online fitness resource you'll ever need. We filter out the BS to ensure you meet your health and fitness goals!

The best online fitness resource you'll ever need. We filter out the BS to ensure you meet your health and fitness goals!

Whole websites and Instagram accounts are devoted to squatting. Traditional, bar-bending squats are considered required by anyone serious about training with weights.

Debate rages on where to place the bar, how deep to go, reps and sets. Squatting has become a religion in the gym. “Bruh, do you even squat” has become a cliché insult.

If squatting the traditional way is so effective (and mandatory), why would anyone do another type of leg exercise?

Turns out that the sissy squat is one alternative that may just be better to develop the quads you’ve always wanted.

It would be easy to assume that sissy squats are easy and not a serious exercise without first knowing the background for the name “sissy”.

Most iron game historians agree that sissy squats are named for Sisyphus, the king of Corinth from Greek mythology who angered the gods and was ultimately sentenced to push a large rock up a hill only to have it roll back down, over and over for all eternity. “Sissy”, so it goes, is a shortened nickname for Sisyphus. (We’re unsure why it’s not spelled Sysy. Go figure.)

A weight-training enthusiast would probably conclude that repeatedly pushing a giant boulder up a hill would have made for a killer leg exercise, completely beast mode, and would have left Sisyphus with Tom Platz-like thighs. Platz himself famously did sissy squats, both free form and on a hack squat machine.

If the traditional barbell squat is dogma, why do sissy squats? Here are three reasons why.

Sissy squats are an isolation exercise, defined as an exercise where only one joint moves. Traditional squats, front squats, Bulgarian split squats, lunges—these are compound exercises made possible only by two or more joints articulating.

Without getting too far into the weeds, for a joint to move, the muscles that articulate that joint must work. In an isolation exercise, only the muscles that attached to that joint are involved. Hence, that muscle is isolated and is doing all the work.

When multiple joints move, muscles that act on every involved joint works. In the case of the squat, the quads do indeed do some of the work, but so do the glutes, the hamstrings, the adductors and the erector spinae (as do other muscles of the back and legs to a lesser degree).

Going a little deeper (figuratively speaking), for the quads to fire, the hamstrings and glutes must shut down. If they did not, the knees and hips wouldn’t bend, because the joints would be held in tension from both sides.

Just like raising or lowering Venetian blinds, one side must relax while the other contracts. Our central nervous system takes care of all of this without our even being aware of it. The phenomenon is called reciprocal inhibition, or reciprocal innervation.

Applying this to squats, at that moment when you feel the glutes activate to get you out of the “hole”, the quads aren’t doing much of anything. The quads are only actually working part of the time.

The muscles and joints that do work throughout a traditional squat are the lower back muscles and lumbar spine. And, because the quads are doing less actual work, more and more weight must be used on the back, putting the lumbar spine at risk of injury.

There’s another reason, and that’s a range of motion (ROM).

During a properly performed sissy squat, the upper and lower legs move very close together. If you were to photograph someone performing a deep squat and a sissy squat, crop the image from the waist up, and turn the photos, you will see the point.

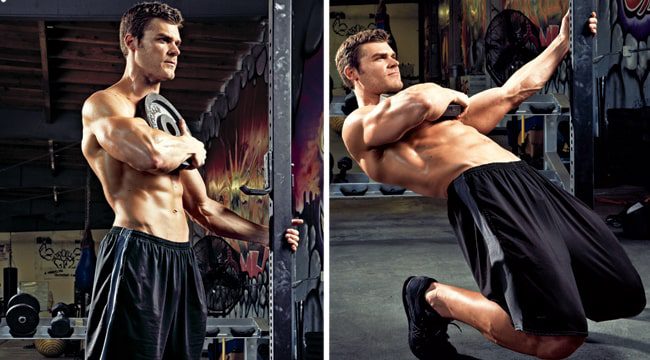

Here’s photo of a man doing a sissy squat:

Now, here’s that very same photo, turned ~75° counterclockwise to show the same ROM if a barbell squat was being performed. That would be a very deep squat indeed, and almost impossible to avoid rounding the back while getting that low.

Then there’s leverage to consider. Using some basic mechanics, the tibia—the lower leg—is the lever arm and the knee is the fulcrum. The more the knee “bends”, the more the muscles that bend it have to work. The closer to parallel to the floor the tibia moves, the more intense the work.

Levers are simple machines that make physical work easier. Crowbars, see-saws, and wheelbarrows are all common examples of levers.

Our bones and joints also form levers. When muscles contract, they exert force on the joint between two or more bones, causing them to move.

In competitive weightlifting and powerlifting, the goal is to move as much weight as possible within the prescribed guidelines of the sport. When it comes to building muscle—whether that be for a bodybuilding competition or for just looking fit—the goal is to build size and definition. That is done by increasing overload, not making lifts easier.

It therefore stands to reason that decreasing leverage and mechanical advantage would be a good thing. Wouldn’t it be better, for example, if a 25-lbs. could get you the same results as a 150 lbs.?

In the world of levers, the farther away a weight is from the force that’s trying to move it, the heavier it becomes. And when we think in terms of resistance training, we know that the more effort that’s required, the greater the “training effect”. Ergo, to make a muscle grow, we should try to make every weight as “heavy” as possible.

One end of the barbell rests in a corner or a hinge, and the other is loaded with weight. Anyone who has done a T-bar row knows that the closer to the weighted end of the bar you grip it, the easier it is to lift, and conversely, the farther backward you go, the harder it is.

Even though the actual weight doesn’t change, the length of the bar in front of you increases the farther back you go, and takes more and more force to move the weight. If you’ve ever experimented with T-bar barbell rows, you understand this without question.

The longer the lever arm, the more strength is required to move it.

The same physical rule applies to sissy squats. The quadriceps must do all the work to move the entire weight of the body from the knees up. The farther the body goes backward, and the lower to the ground the knees travel, the greater the load is magnified. Plus, there’s no question that the quads are doing the work.

Let’s illustrate with an example from an actual human. Let’s say we have a 180-lb. man who is 5’10” tall (70”, using SAE measures). His lower leg is 20” long; His femur (thigh bone) is 15” from knee to hip joint, so from the hip up is 35” for a total of 50” from knees to crown of head.

If our sample man were to do a sissy squat using body weight, using lever math, the distance of the effort (de) would be 20” and the Force of the effort (Fe) would be 150 lbs. for a total load of 3000 lbs., or 1500 lbs. per leg. This is an example of a simple Class III lever.

Traditional squats are examples of compound levers. The lower leg doubles back under the thigh, and the upper body folds over the legs. Every “lever” arm therefore becomes shorter (speaking in engineering terms), and therefore each muscle is doing less work, not more.

Lifting the same amount of weight is easier mechanically-speaking, even though it might feel heavy. This is the opposite of what we should be doing unless of course our goal is simply to lift more actual weight.

Sissy squats are great for people suffering with back problems now, and for preventing future back injury. Even lifters who use excellent form performing barbell squats risk disc herniation or rupture. The stronger you get, the more weight you need to pack on the bar to get achieve muscle overload.

Disc injury (herniation or rupture) is caused when the spine bends beyond load capacity or in an unnatural direction, forcing spongy disc material out from between the vertebrae or causing its casing (the annulus) to rupture. Herniations and ruptures can put pressure on the nerves that provide feeling and empowering muscle contraction in the hips and legs, resulting in debilitating pain, and loss of strength.

Sissy squats place almost no load on the back, although moderate amount of core strength is important though to keep the torso rigid and more-or-less straight during the exercise.

Not all squats performed using “traditional” form inflict potentially damaging spinal load. Light weights and bodyweight squats can be done safely even by people with pre-existing back problems. Bodyweight squats in fact make a great warm-up exercise for sissy squatting.

Regardless of which version squat you opt for, don’t forget to train your erectors. The erectors compose an important part of the core and add stability to the trunk, in and out of the gym.

Great question. Many will, sometimes grudgingly, admit that sissy squats work, and work well.

So, why don’t more people do them? We picked three of the top reasons why more don’t.

We touched on this in the paragraphs above. Bigger weights don’t necessarily mean more growth.

If you’re working legs for other reasons, like metabolic benefit, then squat, lunges, and their variations make logical choices. Just understand the biomechanics and the associated lower back risks, however minor depending on the exercise.

Pound-for-pound, when considering quad development, the sissy squat is hard to beat. If you do sissy squats routinely and correctly, you’re going to see your quads grow and define, assuming your nutrition and sleep are where they need to be.

Few will actually admit it. Many are more interested in putting on an exhibition in the gym than actually training. Unless you’re freakishly, superhumanly strong, you’re not going to be using weights that turn heads when sissy squatting. The only people who will be impressed will be the others around you who’ve tried them, and you.

Even though there’s no bar-bending going on, sissy squats are actually very challenging, even when using body weight only. They are deceptively difficult. And there’s simply not the temptation or ability to put on a show.

Once you give sissy squats a try, if you’re honest with yourself, you’ll likely admit that they hit your quads tons better than any other squat variation.

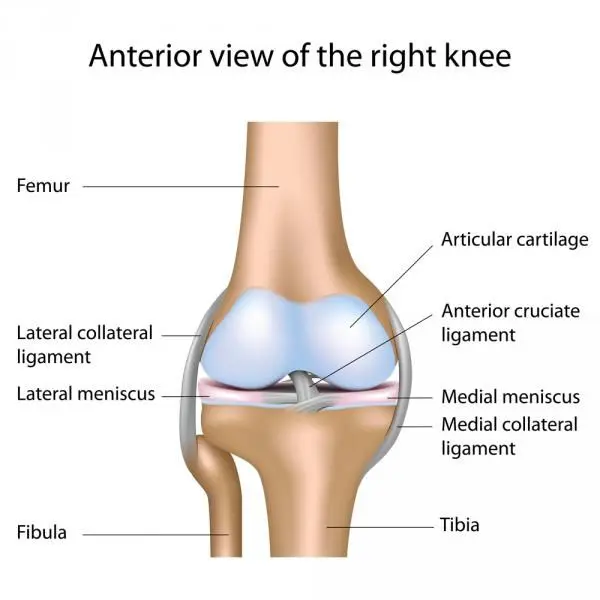

The argument goes that sissy squats initiate a shearing motion between the head of the femur (thigh bone) and tibia (lower leg). It says that when the knee bends far forward over the toes, that the femur freely moves over the head of the tibia, stressing the tendon that holds the knee cap, the patella tendon.

The knee is designed to support heavy loads, sometimes surprisingly large loads. Running, for instance, generates a vertical impact somewhere in the neighborhood of 2.5 to 2.8 times bodyweight.

Using that estimate, a 150-lb person, generates a 400 pound per leg per step impact. So the knee is a robust structure and up to the task of walking, running, jumping and landing, bending, and so forth.

Everyday examples of the knee safely extending far over the toes include descending a steep flight of stairs. In athletics, the extreme knees-over-toes is always seen in a baseball catcher’s, or long-jumpers.

All four heads of the quadriceps share the same tendon. The quad tendon then wraps over the knee cap which is anchored to the tibia by the patella tendon, forming the equivalent of a harness. The patella tendon is one of the thickest in the body.

The femur is securely held in place during knee flexion. Only when there’s existing structural damage would the femur move back and forth over the head of the tibia.

People with pre-existing knee issues should approach sissy squats with caution, although sissies are now part of at least one rehabilitation routine designed to strengthen the knees for extreme athletic performance. If you have concerns about your own knee stability, consult a healthcare professional, like a physical therapist or even an orthopedic surgeon.

Add supplemental exercises for the knees. It’s important to avoid muscle imbalances that put uneven torsion on the joints. Muscles like the tibialis anterior are almost always forgotten, but those forgotten muscles enhance your overall strength and ability in the gym.

There’s always some risk in resistance exercise, but it’s a safe bet that there are far more back injuries caused during traditional squats than knee injuries from sissy squats.

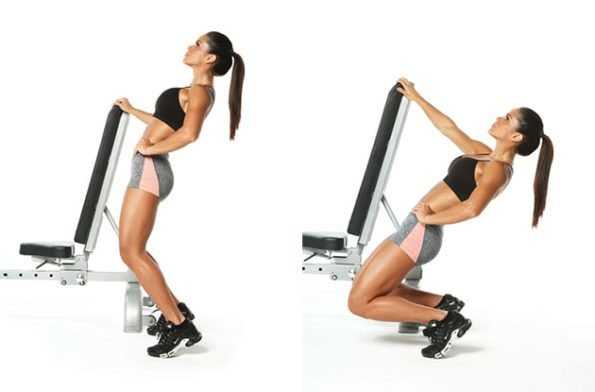

Place your feet shoulder-width apart with toes pointed comfortably in a natural orientation. If your toes naturally point outward a bit, don’t fight it.

Bend at the knees only, tense your entire quadriceps, and gradually roll up on the balls of your feet as you descend, keeping your torso in a straight line with your thighs. Descend straight down (and not forward) with hips over heels until your lower legs are parallel to the floor.

Hold onto a bench or power rack or other stable object with one or both hands to maintain balance if needed, but avoid giving yourself any help descending or ascending until those last difficult reps. You can also use an aerobics step or wooden block to support your heels if you find this adds stability and lets you add weight.

Like the barbell squat, the sissy squat has a “pocket”. You’ll find the pocket when your hips are aligned over your heels. Concentrate on the upper thighs and adductor muscles to help locate it.

A terrific intro to sissy squatting is the Hindu squat.

The easy answer is to just do them instead of barbell squats or dumbbell squats.

A simple pyramid set-and-rep structure, start a high-rep warm-up set or two, a couple of sets using mid-range reps (15-20) and then adding resistance until you finish with a couple of challenging sets of six to eight reps is going to smoke your thighs.

5 x 5 set-rep structures (5 sets of 5 reps) also work well for sissy squats.

For an extraordinary burn, superset sissy squats and leg extensions.

Always warm up the legs beforehand.

A sissy squat bench reduces the performance difficulty of a sissy squat by anchoring the lower legs. The sissy bench removes the balance challenge posed by the freeform version.

A sissy squat done with the sissy bench looks like a leg extension machine in reverse: the lower legs are stationary and body from the knees up move. In actual fact, the same thing happens with the freeform sissy, just not as obviously.

None of this is to say that you shouldn’t be doing barbell or dumbbell squats, or any of the more conventional or popular leg exercises.

Our goal here is to provide you an alternative leg exercise that targets your quads exclusively and may just make your gains come more quickly, giving you that coveted thigh sweep and definition we all want. Who knows? Maybe sissy squats will become your go-to leg exercise.

Once you get bored of the sissy squat, why not try some of its alternatives?