The best online fitness resource you'll ever need. We filter out the BS to ensure you meet your health and fitness goals!

The best online fitness resource you'll ever need. We filter out the BS to ensure you meet your health and fitness goals!

The six-pack. Who doesn’t want one?

Women and men both want washboard abs, the unmistakable look that says “I’m fit” with no further justification required.

Knee raise exercises have become a staple in the gym, reputed for helping develop that coveted washboard middle.

But are they actually good for abs, and if not, then what are they good for?

We’ll look at the science that governs which skeletal muscles actually raise the legs, and where knee raise exercises might fit into a training program.

Why are we even questioning this? There’s a good reason: anatomy and physiology show that knee raises don’t work the abs dynamically.

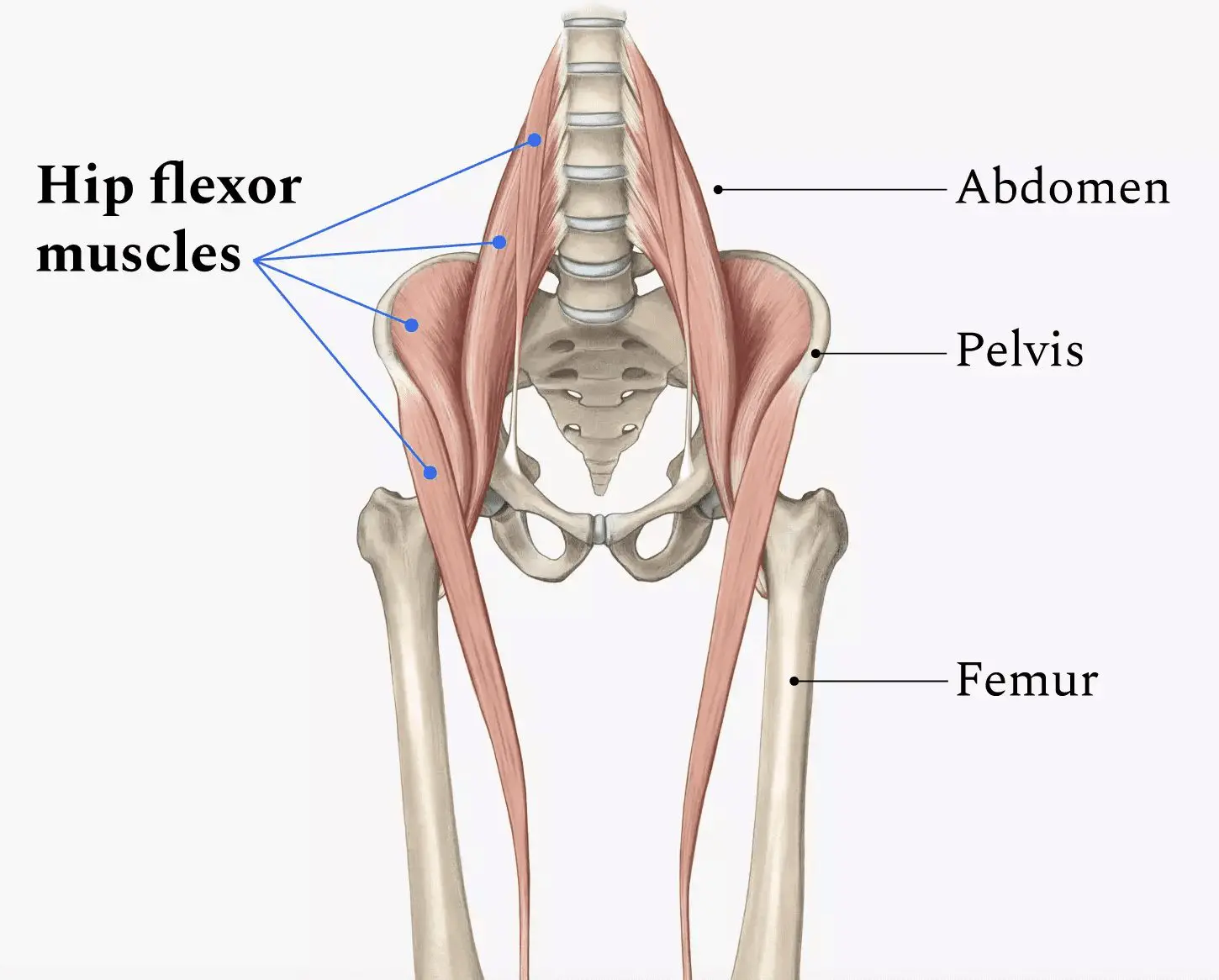

The naked truth is that the abs don’t raise the legs. The hip flexors do.

We’ve all seen persons with chiseled abs doing leg raise exercises. But is it the leg raises that got them those abs? Or is it other exercises they do (and of course good eating habits that clear away the superficial fat to make them visible)?

It helps to take a walk over to the anatomy chart to see which muscles really do the work in a leg raise exercise.

So why exactly is it that we “feel” knee raise exercises in our mid-sections?

Since the abs don’t raise the knees, what’s happening here?

Three factors contribute to that “feel”:

At this point, you may be asking, “what’s wrong with isometrics for abs”?

This is best answered with a comparison.

Say you want to build your biceps. Would you hold a weight steady in one position with bent elbows for one long rep (isometric)? Or would you do curls (dynamic)?

To develop a muscle for aesthetic purposes, it needs to tighten and release back and forth against resistance and not simply remain static under load.

If you want rep work for the abs, the abs must contract and relax in repetition, which means crunches, sit-ups, or otherwise flexing the spine.

Let’s put it to the test. Do leg raise exercises only for six months, and completely stop doing crunches, rope tucks, or sit-ups. Then, gauge the results.

Few would accept this challenge because they’ve been convinced that leg raises are required to supplement crunches and other dynamic ab exercises like sit-ups and rope tucks.

It does turn out that there is some functional benefit to knee raises. Surprise, surprise: they’re good for the hip flexors you see and those you don’t.

Nature dictates if you’ll have a six-pack, an eight-pack, or four-pack. You’re born with a set number of muscular bundles in the rectus abdominus (“the abs).

Once you develop the abs and chisel away superficial fat with good eating habits, you’ll learn how many rows your washboard actually has. If you have four, you’ll never have six, no matter how hard you try. You can’t add abs any more than you can add another muscle to your biceps, or another pec muscle.

People with hip injuries, post-operative hip replacement patients, and older adults who want to work on balance and fall prevention, can all benefit from certain types of leg raise exercises.

There are also some ways to modify leg raise exercises in a way that can meaningfully engage the abdominals. Let’s just be clear that they are not ab-specific and that there are much better ways to spend gym time if the coveted six-pack is what you’re after.

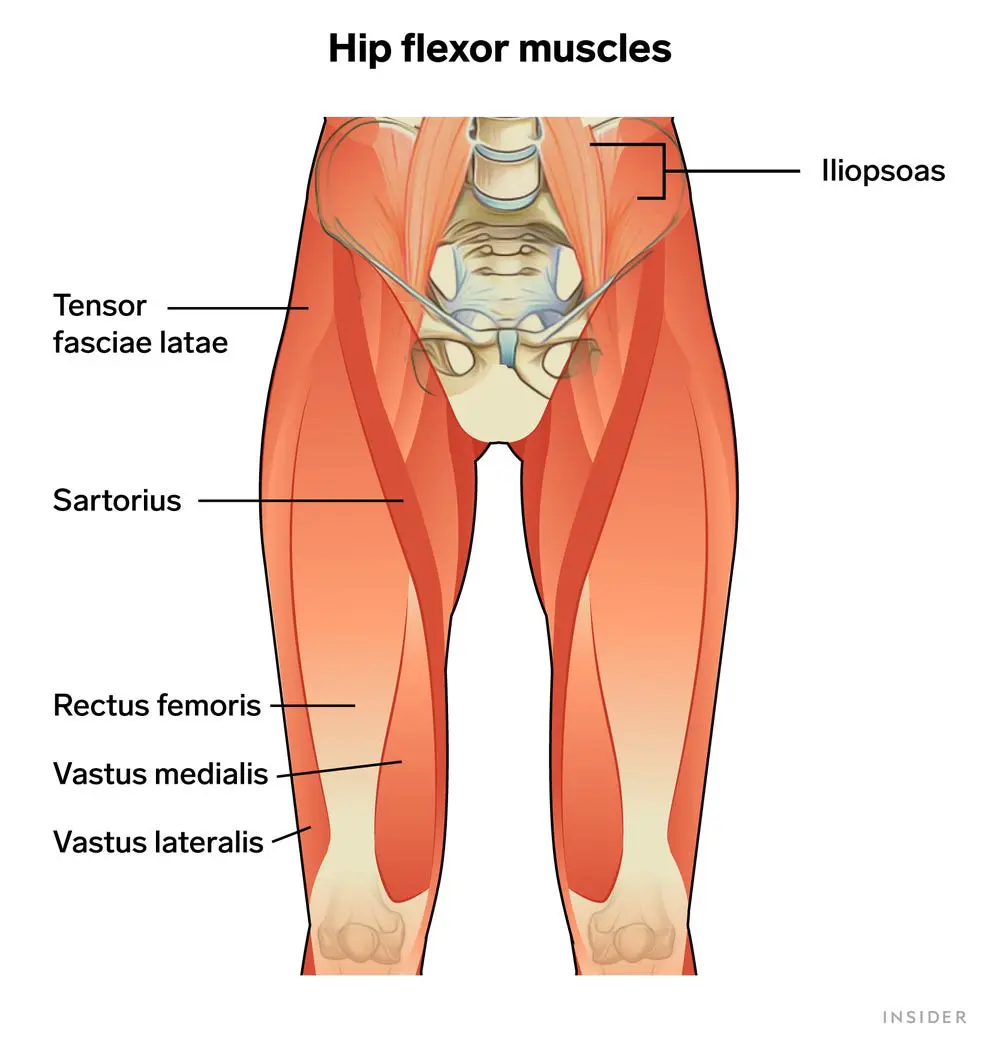

Knee raise exercises can be useful for bodybuilders to target the three visible hip flexors: one of the four quadriceps, the rectus femoris, and two other visible hip flexors, the sartorius, and tensor fascia lata.

The rectus femoris is the V-shaped muscle that pops out when flexing the quads. Interesting fact: the rectus femoris is the only quad muscle that crosses the hip joint.

The sartorius and tensor fascia lata are less conspicuous, although judges at a bodybuilding contest will be looking for them when comparing competitors.

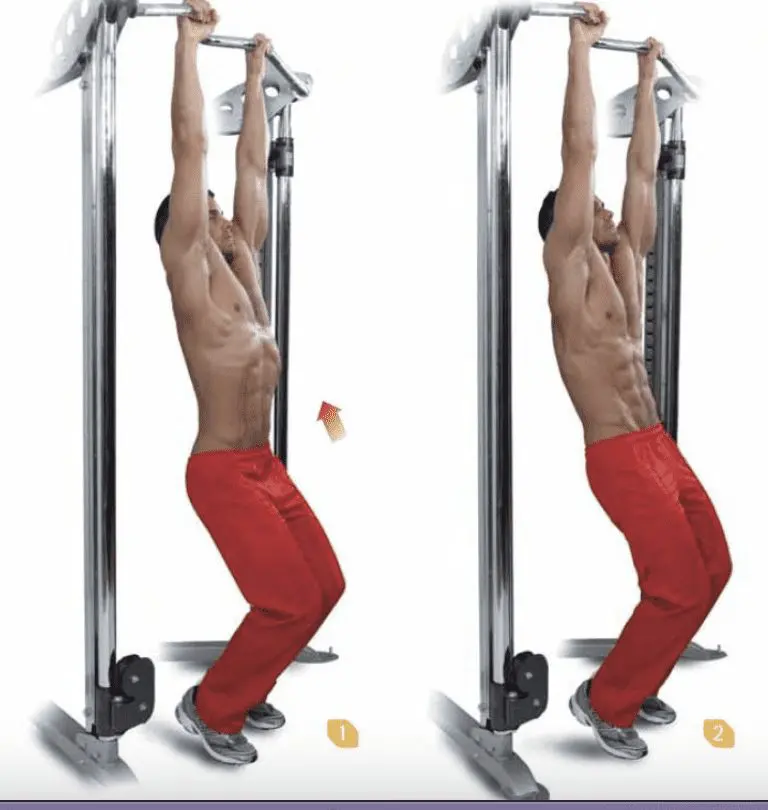

Standing Knee Raises engage the core muscles to help keep the upper body upright and straight, although they are not a good isolator of the abs.

The Standing Knee Raise exercise is a staple for physical therapists. It helps recondition hip flexors during the post-operative recovery period for patients who’ve had a hip replaced, whose hip flexors need to regain good function after the time off and trauma hip surgery includes.

Because the hip flexors are responsible for everyday activities like climbing stairs and getting in and out of a car, deconditioned hip flexors can slow the patient’s return to normal activity.

They also prevent further injury. A weakened hip flexor can lead to tripping with walking over curbs or stair climbing because the foot isn’t being lifted high enough to clear the obstacle.

Standing on one leg—particularly for the single-side version—can help improve balance. Balance work is important for older adults in particular.

You can do a Standing Knee Raise using only the weight of your leg, or you can add an ankle weight for more resistance if needed. You can do them one leg at a time, or alternating legs, which looks like marching only very slowly.

To do the standing knee raise:

A creative knee raise exercise variation is done using a cable machine. The Cable Knee Raise involves moving the knee against resistance.

A nice advantage of the cable knee raise is that it is performed lying on one’s back, which provides the exerciser with the tactile feedback of the floor, signaling if the back is beginning to over-arch.

Here’s how to do a Cable Knee Raise:

Resist the temptation to use too much weight. There are no trophies for personal bests on Cable Knee Raises.

Perform crunches on an incline board with head and shoulders on the upper end for an interesting variation on the traditional crunch.

This leg raise exercise doesn’t isolate the abs as much as the traditional crunch because it’s pretty much impossible to not engage the hip flexors. If you were able to find a way to relax the hip flexors, the legs would add weight and increase the load on the abs.

To perform an Incline Reverse Crunch:

The Hanging Pelvic Tilt is a variation on the Hanging Leg Raise. Its advantage over the Hanging Knee or Hanging Straight Leg Raise is that it only slightly engages the hip flexors. It also poses a mechanical advantage to the abs because the abs must attempt to move the entire weight of the legs.

Think Hanging Knee Raise without actually raising your knees.

Hanging Pelvic Tilt exercises require a pull-up bar or Knee Raise station sometimes referred to as a Captain’s Chair.

To perform the Hanging Pelvic Tilt exercise:

Not technically a knee raise. Unilateral Leg Raises work the hip flexors and reduces the strain on the lower back that two-leg raises impose. Wear an ankle weight to add resistance. Bodyweight alone is plenty if doing these for post-op or post-injury rehab.

Unilateral Leg Raises can be done by repping with the same leg, or alternating legs.

This maneuver engages the abs and prevents the hip flexors from being the only muscles to work during the exercise. The weight of the leg adds resistance.

Knee raise exercises for hip flexors can be programmed into a leg day, or, as an auxiliary exercise on a day you’re focused on another body part.

A third and interesting programming option is in whole-body routines that specify each body part receives some attention during each workout. The Hardgainer Solution for example stresses working each major body part each day, multiple days per week, but in different ways, so that muscles recover optimally.

Do weighted Standing Knee Raises toward the end of your workout, once you’ve finished the heavier stuff.

Using a lightweight (<=20 ankle weight), do 2 to 3 sets of 10-20. You’ll feel the burn quickly.

You can insert Standing Knee Raises anywhere in a workout that you’re not focused on legs. I like them at the beginning or end.

The same set and rep tactics apply as above. Nothing too heavy, using moderate to high reps.

If you’re working out four or more days a week and spreading your exercises among body parts, you can insert leg raises as your leg exercise on one of those days.

Here’s an example2 of how that might look in one whole-body workout, using two of the knee raise exercises we’ve described:

1a) DB Incline Press 5-6 X 6

1b) GPP for lower body

2a) Standing Knee Raises 5 X 10-12

2b) DB or BB Upright Rows 5 X 15-20

3a) Pull-downs Behind the Head 5 X 12-15

3b) Two-Arm DB Curls 4 X 20

4a) One-Arm DB triceps extension 4 X 10-12 EA

4b) Incline reverse crunches 4 X 12-20

Athletes whose sports require bilateral knee raises—such as gymnasts or divers—can benefit from the Hanging Knee Raise. The iron cross ring exercise in gymnastics and pike position dives, for example, both require strength and control of the muscles that knee raises work.

Hanging Knee Raises can be done with bodyweight only, or by adding weight using ankle weights or a medicine ball.

Too much of a good thing can be bad.

The hip flexors get a lot of work doing everyday things like mentioned above: getting in and out of an automobile, climbing stairs or ladders, and even more in the gym, particularly on cardio machines.

Because the hip flexors exert tension between the thigh bone (femur) and the lower back (lumbar spine), over-developed hip flexors can place constant stress on the lower back, rolling the pelvis forward and creating over-arching of the lumbar spine. That condition, called hyper-lordosis, can lead to disc bulging or herniation, which in turn can create pain, weakness, and numbness down one or both legs.

Knee raise exercises primarily work the hip flexors. They’re useful for bodybuilding routines, hip rehab, and athletes whose sports rely on moves that raise the knees.

Knowing what they work well for, and when to apply them in a program, assures you’ll use them beneficially.